A mock—up of the Erebus, a ship trapped by ice in 1848. Nattilik Cultural Heritage Center, Gjoa Haven

“The color of the Navy”

The loss of the ships Terror and Erebus was the largest Arctic disaster in history. However, it is still unclear exactly what happened to the detachment of 129 polar explorers. A new genetic study opens the veil of mystery. The identity of the victim eaten by British cannibal sailors has been established.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the British made several attempts to find the so-called Northwest Passage — a sea route from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. The expedition of John Franklin in 1819-1822 was especially famous. The polar explorers returned by land, feeding mainly on lichen. And one day the head made an entry in his diary: “It was not possible to find lichen, so we drank tea and had dinner with our shoes.”

Franklin undertook his fourth and last expedition in 1845. She was supposed to complete research on the American Northern Sea Route. Two ships were equipped — “Terror” and “Erebus” — wooden sailboats with engines from steam locomotives. The reserves were taken for five years.

There was no news from the polar explorers for a long time — in those days it was normal, since radio communication did not exist. However, in 1848, Franklin’s wife still managed to get the Admiralty to organize a rescue operation. At one point, 13 pennants participated in the search at the same time.

The first graves of the missing were found in 1850. A few more years later, the searchers met the Eskimos, who showed them items from the Terror and Erebus. They learned from the aborigines that the crew members resorted to cannibalism. Victorian England was shocked, many refused to believe that the color of the country’s navy could descend to such a level.

Later studies confirmed this: knife cuts and traces of cooking were found on the bones. It is unclear how the polar explorers died — by their own death or at the hands of other crew members.

The last note

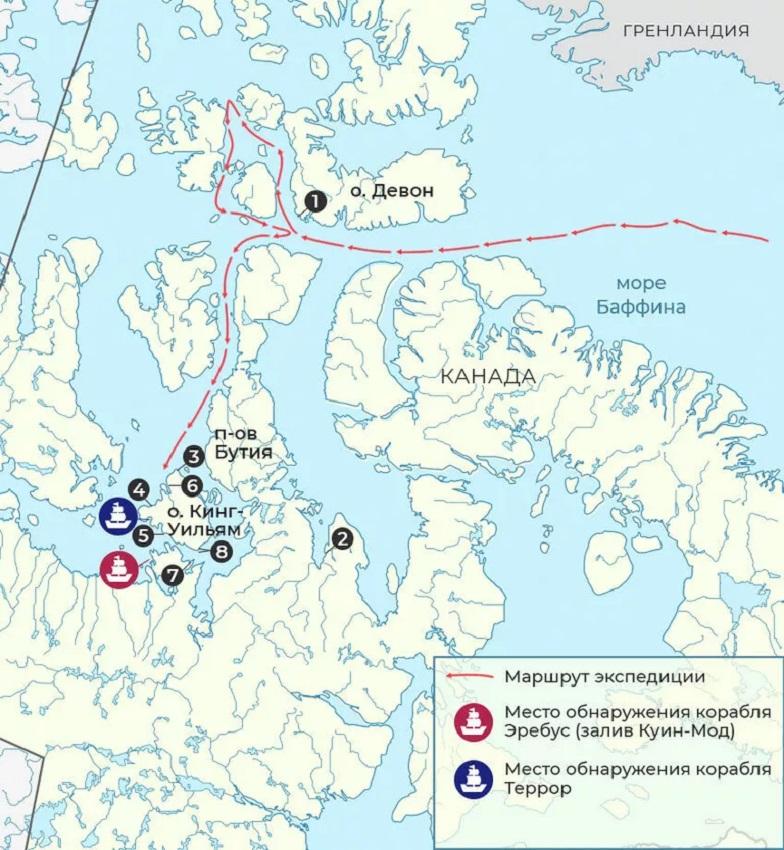

It also turned out that the participants of the expedition left notes along the way, including in special pyramids made of stones. Thanks to these and other findings, it was possible to roughly reconstruct the course of events.

The ships were stuck in the ice in the Larsen Strait for two years. During this time, 24 people died, including Captain Franklin. He was replaced on the Erebus by James Fitzjames, an ambitious combat officer, the illegitimate son of a high-ranking diplomat.

He was most likely the author of the last known message of the expedition. A note left on King William Island stated: “Sir John Franklin died on June 11, 1847, and the total losses of the expedition to date have amounted to nine officers and 15 sailors…[We are] leaving tomorrow, the 26th, towards the Bak River.”

The sites of the main finds of the John Franklin expedition. © Illustration by RIA Novosti.

They hoped to reach people by this river. In April 1848, 105 sailors set off. They dragged boats with supplies. Then they found 35 places with human remains. The farthest from it is 400 kilometers away, on the Adelaide Peninsula.

As usual, a whole set of adverse circumstances led to the disaster. Captain Franklin did not choose the most successful route. The equipment did not quite match the Arctic cold. The team was plagued by various diseases: tuberculosis, botulism, scurvy.

In addition, high levels of lead have been found in the hair of the deceased these days. This is due to poor-quality cans or a water distillation system. Toxic metal weakens not only the immune system, but also human cognitive abilities. It is possible that this affected the quality of the expedition’s management.

However, none of the reasons for what happened is exhaustive — it contributes to the emergence of various conspiracy theories, as well as inspires writers and filmmakers.

“An incredible level of desperation”

The tragedy is being investigated to this day. “Terror” and “Erebus” were discovered at the bottom of the sea in 2014 and 2016, respectively. And in 2017, scientists called on the descendants of those who participated in the ill-fated expedition to respond in order to use genetic tests to determine who the remains belong to.

That’s how 25 people were identified. Including John Gregory, a midshipman from the Erebus. His descendant Jonathan Gregory lives in South Africa. The family still keeps the memory of the deceased polar explorer.

Now, with the help of genetics, an important new discovery has been made. Anthropologist Douglas Stanton from the University of Waterloo and his team have determined that one of the lower jaws with traces of cuts is James Fitzjames. That is, subordinates most likely ate it.

“It was cannibalism for the sake of survival. They must have experienced an incredible level of despair. But, unfortunately, such drastic measures only prolonged the suffering of those people,” says Stanton.

The more new information there is, the more questions arise. It is noteworthy how many officers, including senior ones, died during the expedition. What exactly happened to the participants of the desperate campaign on land, we can only guess.