The Chelyuskin ship, 1933. © TASS

Chelyuskin Expedition

The Arctic expedition on the icebreaking steamer Chelyuskin, which eventually became known to millions of people around the world, was very important for the country. In 1932-1933, the Soviet Union’s research activities in the Arctic were so extensive that it allowed the country to become a leader among other states claiming Arctic territories.

The world’s northernmost polar station was opened on Rudolf Island, stations at Cape Zhelaniya, Cape Chelyuskin, Koteln Island, and Cape Severny. The research was conducted in almost all seas of the Soviet Arctic. The Chelyuskin expedition was supposed to consolidate the traffic pattern along the Northern Sea Route (NSR), which was already given special importance at that time.

The task of the Chelyuskin expedition was to complete the Northern Sea Route in one navigation. This road was needed to supply the Far East and Siberia with all the necessary goods. In addition, the expedition on the icebreaking steamer Chelyuskin was supposed to provide experience of passage through the NSR on a non-icebreaking class ship.

A year before Chelyuskin, the Soviet icebreaker Alexander Sibiryakov successfully passed from Arkhangelsk to the Bering Strait, and immediately after this success, the Main Directorate of the Northern Sea Route, Glavsevmorput, was formed, whose tasks included mastering the NSR, creating settlements and infrastructure along it. Otto Schmidt became the head of the Main Northern Sea Route.

Otto Schmidt is an encyclopedic scientist, Arctic explorer and Pamir conqueror. He studied subjects so deeply that he often became a pioneer. It was thanks to him that the Great Soviet Encyclopedia began to be published. Exploring the Arctic, he discovered new lands. However, perhaps his most famous project was the Chelyuskin expedition

No one could have known then that the Chelyuskin expedition, despite the fact that the ship itself sank, was destined to glorify him and other participants all over the world, but also to emphasize the scale and fundamental nature of the USSR’s work in the Arctic, as well as the skill and superiority of Russian aviation. For the first time in the history of Arctic exploration, an expedition, moreover, so numerous, was completely saved.

Before the expedition, the ship passed from Leningrad to Murmansk in order to eliminate the detected defects and finally form a team. On August 10, 1933, Chelyuskin set off on an expedition. The ship left the Murmansk port at 04:30 without much fanfare and headed for Vladivostok. There were 53 crew members, 29 expedition members, 18 winterers of Wrangel Island, and 12 construction workers on board.

Unexpected drift and death of Chelyuskin

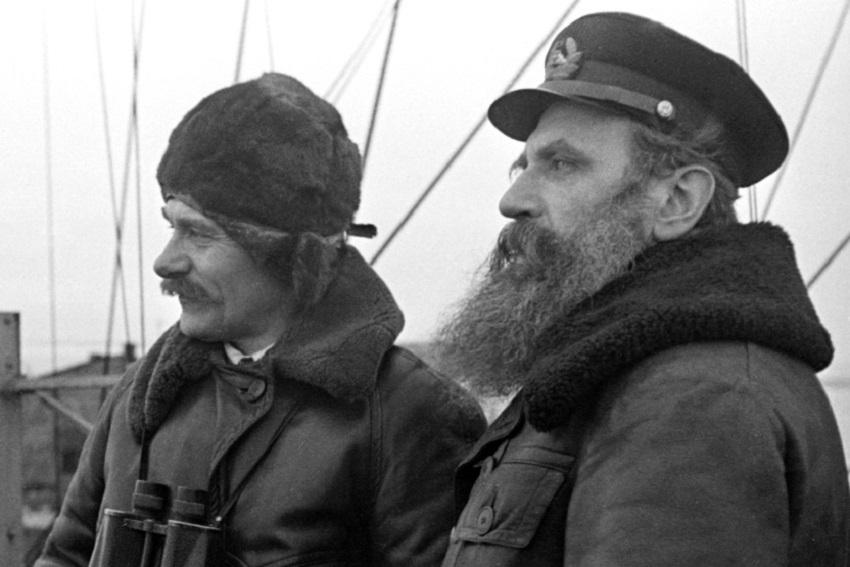

Vladimir Voronin and Otto Schmidt. © Sergey Loskutov/ TASS

At first, everything was going well: Chelyuskin was clearly on the route. However, in the Kara Sea, a hull deformation and a hole appeared on the ship, and on August 13, 1933, a leak formed. In September, when the Chelyuskin was already in the Northeast Sea, due to the heavy ice that appeared, the ship received two more dents on both sides. The leak has increased.

However, by the beginning of November 1933, the steamer had almost completed the planned route and entered the Bering Strait. On November 6, 1933, a radiogram was sent to Moscow informing about this fact and that the steamer was located near Diomede Island, about 20 km from free water. However, Chelyuskin residents failed to reach the water and walk freely to Vladivostok, as planned.

The ice began to move in the opposite direction, the Chelyuskin was pinched, and the ship, already badly damaged, was again carried out into the Chukchi Sea. As a result, Chelyuskin froze into a large ice floe and drifted with it for several months. The expedition understood that the ice could start moving at any moment and crush the ship, which eventually happened.

By the end of November, fears that Chelyuskin would not get out of the ice began to strengthen, and planes designed to rescue people were delivered to Providence Bay from Vladivostok. On February 13, 1934, 144 miles from Cape Uelen and 155 miles from Cape Severny, Chelyuskin sank in 2 hours, crushed by ice. Polar radio operator Ernst Krenkel sent a radio message to Moscow about the loss of the ship.

104 people, including ten women and two children, managed to get on the ice. Earlier, the rest of the expedition members left the ship near Cape Chelyuskin for various reasons, mainly due to illness. Captain Voronin and expedition leader Schmidt were the last to land on the ice floe. Only Boris Mogilevich died: he hesitated on the deck of the ship and was crushed by a barrel.

Chelyuskintsy on an ice floe

Chelyuskintsev camp, 1934. © TASS

The members of the polar expedition had to spend the period from February 13 to April 13, 1934 on an ice floe. They managed to arrange a “tolerable” life, which everyone tried to make “as culturally and better as possible” (Schmidt). A wooden barracks was built in the “ice camp” thanks to the lumber salvaged from the ship. A bakery was built and even the editorial office of the wall newspaper “Don’t give up!” was organized.

The airfield was being prepared in the camp, despite the fact that the ice was covered with cracks, hummocks, drifted with snow and constantly broke. The expedition received radio messages informing about the organization of rescue and all activities. “We were sure that we would be saved,— Schmidt later wrote.

The fate of the Chelyuskinites was watched, without exaggeration, by the whole world. And if the expedition itself glorified the polar explorers, then its rescue was a triumph for polar aviation and the acquisition of invaluable experience in using aircraft in the harsh and unpredictable conditions of the Arctic.

A list was drawn up at the camp, according to which women and children were to be brought ashore first. “The women, who were doing great on the ice floe, were very reluctant to see themselves in a privileged position. The publication of the list caused a lot of upset, as those scheduled for an earlier dispatch strenuously proved that they could give up their turn to others.

Anatoly Lyapidevsky’s crew was the first to land in the Chelyuskintsev camp in the spring of 1934 on an ANT-4 aircraft. The searches were conducted in conditions of increased complexity: It was a polar night, with strong winds and blizzards rising every now and then, and temperatures dropping to 40 degrees.

Lyapidevsky’s plane took off 28 times in search of an expedition and only found it on the 29th. Moreover, the pilot managed to land his car on the site, which was three times smaller than it was necessary. Then pilots Slepnev, Kamanin and Molokov arrived to help. During rescue operations, the pilots were required to exert the highest effort and resources of the body. It was a real feat.

While intensive work was underway in the USSR to rescue the expedition, the Western media spread false information and spread panic. However, all the pessimists had to admit they were wrong. By April 13, 1934, the Chelyuskinites were saved. The pilots were awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, and the polar explorers were awarded the Order of the Red Star.

Despite the fact that Chelyuskin failed to enter the Pacific Ocean, the main goal was achieved — the NSR’s cross-country capability was proven. In addition, it became clear that it was necessary to increase the arsenal of the icebreaking fleet and correctly position vessels on all sections of the route. Navigation experience was also gained: conclusions were drawn about the design of steamships for the Arctic.

By Yulia Ostrogozhskaya and Irina Skalina