Nagursky Ya.I. on Novaya Zemlya. A drawing of the Central Documentary Film Studio.

First flights in the Arctic

Nagursky’s first flights to the Arctic, which took place in 1914, were almost ten years ahead of the appearance of the Swiss pilot Mittelholzer’s aircraft in the northern sky off the coast of Svalbard, and only in 1924 the domestic pilot B.G. Chukhnovsky flew around Novaya Zemlya on a float plane. But these were already quite advanced aircraft, and in 1914 Nagursky had only a fragile Farman aircraft at his disposal.

Any strong gust of wind could dump her into the waters of the cold Barents Sea or throw her onto the glaciers of Novaya Zemlya. In addition, then I had to fly blindly, sometimes in fog, not knowing the weather conditions on the highway, having no connection with people on the mainland and not hoping for any help in case of an accident.

It should also be noted that at that time the cabins of the aircraft were open, and the pilots did not have particularly warm clothes. Now the name of Jan Iosifovich Nagursky is known only to a narrow circle of Arctic historians. The point on the geographical map, named after the first conqueror of the Arctic sky, the Nagurskaya polar station, located on the island of Alexandra Land in the archipelago of Franz Josef Land, tells the reader little.

The Farman with an 80 hp engine could carry only about 350 kg of cargo, reaching a speed of no more than 90 km/h. Therefore, they took only the most necessary things — warm clothes, food and rifles, leaving many useful things at the assembly site of the aircraft. So, on August 8, 1914, the flight was north along the western coast of Novaya Zemlya at an altitude of 800-1000 m; the temperature outside was about minus 15 ° C.

Nagursky was amazed and fascinated by the landscape that opened up under the wing of his plane: “The heavily loaded plane barely rose above the ice, but then began to climb rapidly; more and more beautiful views opened up in front of us… Picturesque, fantastically shaped icebergs sparkled with ice tops. They were arranged in straight rows, then randomly scattered; in shape, some resembled slender obelisks or prisms; others were strange—looking driftwood.

All of them sparkled, as if sprinkled with millions of diamonds, in the rays of the setting sun. The knowledge that I was the first person to board an airplane in this harsh land of eternal winter filled me with joy and anxiety, made it difficult to concentrate.”

But the anxiety and uncertainty soon passed, and Nagursky settled into the Arctic sky, although sometimes visibility was very poor. Up to and including August 30, Nagursky made several more flights. The next day, it was decided to stop further flights.

During the flights, the plane froze to the ice floe, and it was snowed in. The pilot was caught in severe storms and sometimes went off course. The plane flew in fog and froze quickly: ice covered not only the wings and tripwires, but even the glasses and clothes of the pilot. It was a real feat.

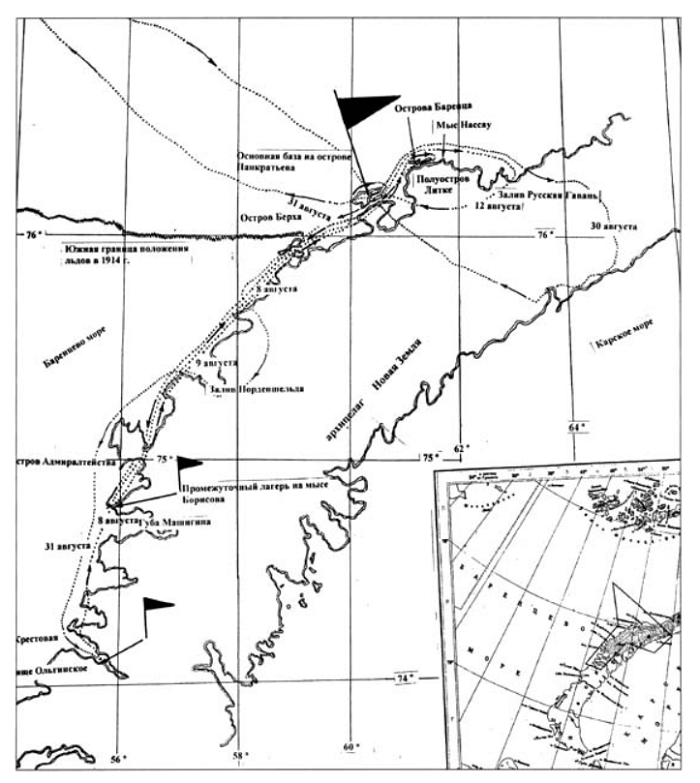

A map of the first flights in the Arctic.

The first aerial photography in the polar regions

During the preparation of the next expedition in the Arctic in 1923, the polar explorer Amundsen decided to call for the help of pilot Haakon Hammer with a Junkers aircraft with skis and floats. It was called the “Ice Bird”. However, when testing the skis installed on the Junker, the aircraft was severely damaged. While it was being repaired, the optimal time for entering the Arctic came out, and Amundsen canceled the expedition.

Then they decided to use the plane for an aerial survey of the Grenfjord area. The expedition’s flights began on July 5, 1923 and lasted for two days. The longest and most important flight turned out to be the last one. The Neuman-piloted “Ice Bird” rose from the Grenfjord on July 7. Flying over the Isfjord and Billen Bay, she penetrated into the central part of the New Friesland Peninsula and arrived at Loma Bay.

Then, heading north, the “Ice Bird” reached Sorge Bay. Over Whale Island, the plane crossed the 80th parallel. There was enough gasoline to proceed to Cape Severny and even further to the 82nd parallel. But due to the irregular operation of the engines, we had to return back to the Gren Fjord, walking along the northwestern shores of Svalbard.

During the research, aerial photography in the Arctic was carried out for the first time in history. And on July 15, 1923, the expedition boarded a coal tanker and returned to their homeland.

The first aerial survey of Arctic animals

Junkers Yu-13 aircraft

In 1927, Dorofeev S.V. and Freiman S.Yu. were the first to apply the aerial photography method to account for the Harp seal of the White Sea population (Dorofeev, Freiman, 1928). The expedition took place from February 23 to May 15. Aerial photography of the oil deposits was carried out by the Potte apparatus from a 6-seater Junkers type U-13 aircraft. 4 people participated in the flights: a pilot, a flight mechanic, a navigator and a researcher.

The essence of the method was as follows:

1) by means of multi-route aerial photographs, the average density of seals was determined at each deposit;

2) by circling the deposits, their area was determined;

3) extrapolated the average density for the entire deposit;

4) using data from fishing vessels, the proportion of adult males in the deposits was determined;

5) assuming that males accounted for 25% of the population, the number of Harp seals was calculated.

The flight altitude was 800 m, and the average speed of the aircraft was 120 km/h, however, practically due to strong winds, it varied from 50 to 200 km/h. The film reel had 50 negatives with a picture size of 13 x 18 cm, and the film stock was unlimited. The sides of the image corresponded to 490 x 680 m of the ice surface, however, due to longitudinal distortion (on average 25%), the size in the direction of flight was 370 m.

The weather conditions were unfavorable: frequent storms and fogs, low clouds and snowfall interfered with work. In addition, force majeure circumstances occurred: an accident and repair of the aircraft, which caused 2 weeks of research work to be lost. There were 26 favorable working days during the expedition, but only a few days could be used for shooting.

The expedition began with reconnaissance flights, and only on March 25 was a test shot taken. Further, there were only 6 shooting days until May 4, while successful accounting samples were obtained only in 4 cases. Therefore, in 1927, only a part of the deposits were photographed, and the number of seals on them in 700 thousand heads was calculated. Since not all deposits were removed, a minimum of 1,050 thousand heads was accepted.

However, according to various researchers, the sex and age structure on lineal deposits is different – there were at least 1.5 times more mature males. Perhaps the females, who were more exhausted during puping and feeding their cubs, began to go into the water more often for feeding or go foraging earlier.

In 1928, the surveys were repeated, but their data and calculations were not published. It was only in 1939 that Dorofeev wrote that in 1928, according to their calculations, the White Sea seal population numbered 3-3.5 million heads. The estimate of the number corresponded to the maximum to the mainstream of that time about the inexhaustible reserves of the seas. Since then, this figure has appeared as a result of accounting in 1928.

Taking the geometric and arithmetic mean of two different estimates: the minimum of 1.05 million heads and the maximum of 3.5 million heads, we get a realistic value of 1.9-2.3 million Harp seals of the White Sea population .

Despite difficult weather conditions and force majeure, aerial photography in 1927-28 provided rich material and revealed the undoubted value and prospects of this method for animal research not only in the Arctic, but also in other regions.

By Nikolay Kuznetsov

Source: Dorofeev S.V., Freiman S.Yu. The experience of quantitative accounting of stocks of the White Sea herd of Harp seals by aerial photography // Tr. NIRKH, vol. 2, issue 4, 1928. – pp. 5-28.