In the Arctic, the freedom to travel, hunt and make day-to-day decisions is profoundly tied to cold and frozen conditions for much of the year. These conditions are rapidly changing as the Arctic warms. The Arctic is now seeing more rainfall when historically it would be snowing. Sea ice that once protected coastlines from erosion during fall storms is forming later. And thinner river and lake ice is making travel by snowmobile increasingly life-threatening.

Ship traffic in the Arctic is also increasing, bringing new risks to fragile ecosystems, and the Greenland ice sheet is continuing to send freshwater and ice into the ocean, raising global sea level. In the annual Arctic Report Card, released Dec. 13, 2022, we brought together 144 other Arctic scientists from 11 countries to examine the current state of the Arctic system.

We found that Arctic precipitation is on the rise across all seasons, and these seasons are shifting. Much of this new precipitation is now falling as rain, sometimes during winter and traditionally frozen times of the year. This disrupts daily life for humans, wildlife and plants.

Roads become dangerously icy more often, and communities face greater risk of river flooding events. For Indigenous reindeer herding communities, winter rain can create an impenetrable ice layer that prevents their reindeer from accessing vegetation beneath the snow.

Arctic-wide, this shift toward wetter conditions can disrupt the lives of animals and plants that have evolved for dry and cold conditions, potentially altering Arctic peoples’ local foods.

When Fairbanks, Alaska, got 1.4 inches of freezing rain in December 2021, the moisture created an ice layer that persisted for months, bringing down trees and disrupting travel, infrastructure and the ability of some Arctic animals to forage for food. The resulting ice layer was largely responsible for the deaths of a third of a bison herd in interior Alaska.

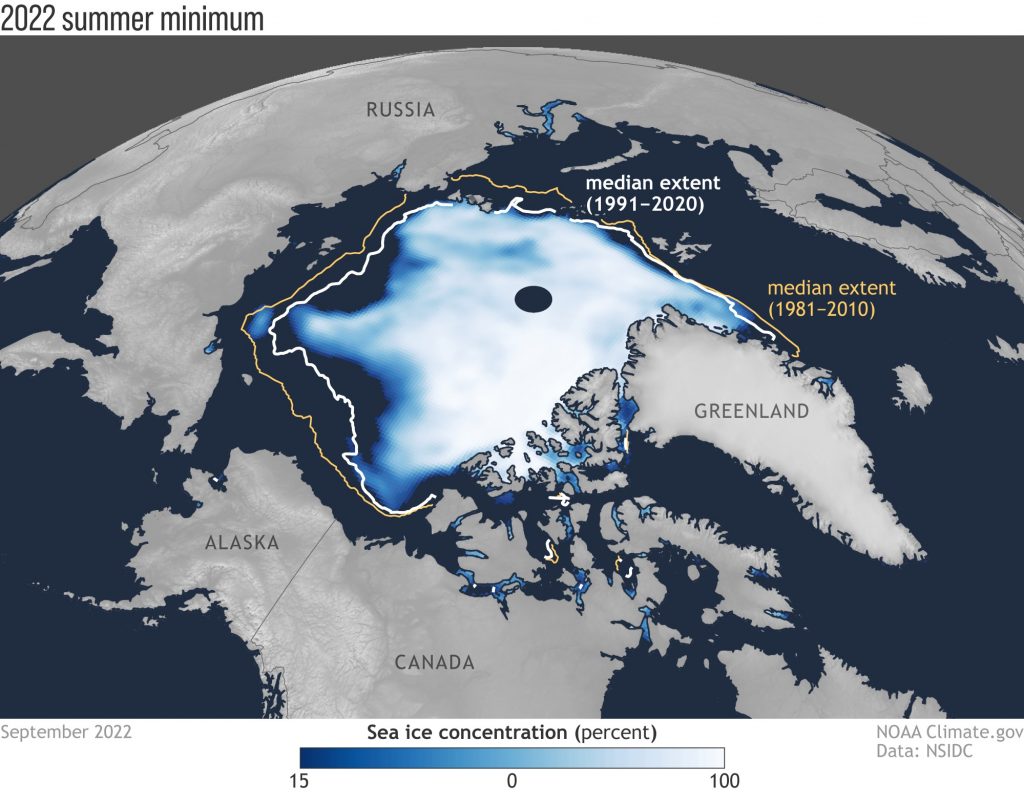

There are multiple reasons for this increase in Arctic precipitation. As sea ice rapidly declines, more open water is exposed, which feeds increased moisture into the atmosphere. The entire Arctic region has seen a more than 40% loss in summer sea ice extent over the 44-year satellite record. The Arctic atmosphere is also warming more than twice as fast as the rest of the globe, and this warmer air can hold more moisture. Snow is also a travel platform for hunters and a habitat for many animals that rely on it for nesting and protection from predators.

A shrinking snow season is disrupting these critical functions. For example, the June snow cover extent across the Arctic is declining at a rate of nearly 20% per decade, marking a dramatic shift in how the snow season is defined and experienced across the North.

Even in the depth of winter, warmer temperatures are breaking through. The far northern Alaska town of Utqiaġvik hit 40 degrees Fahrenheit (4.4 C) — F above freezing — on Dec. 5, 2022, even though the sun does not breach the horizon from mid-November through mid-January.

Fatal falls through thin sea, lake and river ice are on the rise across Alaska, resulting in immediate tragedies as well as adding to the cumulative human cost of climate change that Arctic Indigenous peoples are now experiencing on a generational scale.

The impacts of Arctic warming are not limited to the Arctic. In 2022, the Greenland ice sheet lost ice for the 25th consecutive year. This adds to rising seas, which escalates the danger coastal communities around the world must plan for to mitigate flooding and storm surge.

By Matthew L. Druckenmiller, Rick Thoman, Twila Moon Original